Outlets Gone Wrong

"Simple" wiring

We are not always called upon to expound on the “obvious,” except maybe by kids who ask the oh-so-dumb questions, that we_just_don’t have the answers to. Case in point, what’s in a wall outlet? 120, right? Well, maybe.

It’s a case that is so obvious that we may have forgotten how we came to know this.

Taking the point a step further, for “earthing” applications, related to conductive fabrics, or “grounding” relative to appliances, ground is always ground, and it’s safe right?

Well, maybe, unless it has 120, or maybe it’s neither of the two . . .

How can you know? With a little measurement, and thinking out of the box.

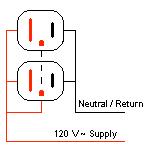

By standard convention, the configuration above is what you should expect, but may not always find to be so.

In this case the short slot should have 120 Volts relative to anything else. If, and only if, you are not in contact with anything else electrically conductive, and somehow touch this 120V, you’ll live to tell about it. Take joy in the fact that you survived death. This time.

The long slot is the return path for any Current you use. In order for current to flow, something must actually be turned on. So if you plug a desk lamp into that outlet, nothing will happen, until you actually turn the lamp on.

Whether you use a two or three-wire power cord, the current flow is always supposed to be between the short slot and the long slot, through whatever you just plugged in. The third hole, the almost round one, is the ground. This is a protective feature, and is intended to never have current flowing through it.

If the ground comes in contact with the neutral, some of the return current will flow through the ground, and the device will still work (producing an alternating magnetic field, somewhere), unless a GFCI breaker or outlet is feeding power to this one, in which case the power will be cut off. GFCI breakers or outlets measure the current through the 120V and the neutral / return wire, and if they differ by more than about 6 mA (milliamps) from each other, power is cut off.

If the ground comes in contact with the 120V, an immediate protective action should occur, such as a fuse blowing, or a breaker tripping open / off.

That’s the end of the normal stuff. Things now get interesting.

I visited a client who had a tower computer, where the computer proper sat on the floor, and the keyboard, display, and mouse were on her desk. She had aluminum foil wrapped on top of the computer, because she felt it irritated her. How could she have known? I connected a meter to a reliable zero voltage reference and found the computer case to be at 60V!

She had the computer’s three-wire power cord connected to a three-prong outlet, so how could this be?

If you had one of those three winky-blinky LED testers as shown, and plugged it in, you’d have gotten the message: no ground.

Well, I didn’t have one of those fancy testers, so I got out my screwdrivers, carefully extracted the outlet from the wall, and found it wired as above. Well, not exactly. The ground wire was not disconnected, it just wasn’t there. You see, despite appearances to the contrary, this was a very old house, electrically. During the initial install, some 70 years prior, they used two-wire cables for all power and light. So this client’s computer, not having a proper ground reference connected to its case, “floated” to the average of the two wires feeding it, or 60V. Now, mind you, this could have been a three-wire cable, and the ground not connected as shown above, as I found in another home for the fridge, which was exhibiting the same phenomenon. In that case I just connected the ground wire.

Not wanting to rip open the walls to install new wiring, just like the electrician who preceded me that installed three-prong outlets to make the home look up-to-date, I installed a workaround, as above. Whenever you draw current, the 120V is not capable of infinite current, so the voltage drops a bit, in this case to 118.5. But the same thing happens to the return wire, and since it cannot go below zero, as that would put it in a different universe, it acquires a voltage it did not previously have, in this case 1.5. So in connecting the ground lug to the return lug, the case of the computer dropped from 60V to 1.5V, a slight improvement, I’d say.

If you had one of those three winky-blinky testers as shown above, and plugged it in here, it would tell you all is well.

Things are going to get more interesting.

If by chance the 120V was not in the short slot, and I’d installed the workaround I used just before, I would have accomplished the above. I found this at a home just by chance and curiosity, when the occupants told me they’d bought a “grounding” mat to reduce electrical stress, and for whatever reason chose not to use the electrical “ground.” The mat’s recommendations suggest using the ground lug.

On a similar note, a vendor that sells a Body Voltage (BV) kit, to identify the field potential acquired due to structural cavity wiring, suggests to use the ground lug. I wonder what those values would be, if instead of the zero reference you use 120V . . . Measurement biased?

For those contractors that use multiple appliances for remediation, like from water intrusion or mold, plugging something into one of these will make the case of the appliance have 120V on it. Small matter, until, and if, you simultaneously touch another appliance that may be properly grounded, and it then puts your lights out . . .

If you had one of those three winky-blinky LED testers as shown above, and plugged it in here, it would tell you all is well. But all is definitely Not well. So take that that winky-blinky tester and toss it out the window, ensuring you don’t hit someone with it, as your insurance doesn’t cover for that.

So to employ the workaround, you need to be absolutely sure which is the 120, and which is not. How can you know? All metering that uses two leads displays a difference between one lead and the other. So you plug the two leads in various arrangements into the above mis-wired outlet and you will get 120V between the short and the long slot (normal), 120V between the short slot and the almost-round hole (normal), and zero between the long slot and the almost-round hole (normal). So your state-of-the-art digital multimeter told you everything is normal. But it is definitely Not. Don’t throw it out, as it’s heavier and could do more damage, and your insurance doesn’t cover this either. You just did not use it to its fullest extent.

Using the sketch above, while holding one lead so you touch its metal tip, plug the other lead into each respective hole, looking for AC voltage. Using “floating detection,” because your body “floats” to some voltage, to make the meter detect the difference, the 120V will be displayed on your meter.

But you may rightly think: if I touch the lead’s metal tip, there will be voltage on it. Well, almost. The meter’s internal resistance is 10 million Ohms. If you were properly grounded while you touched that lead, and the other was stuck on the 120, the current flow would be 120 / 10 million = 12 microAmps. You will not feel it, nor be injured by it. If you were not grounded at all, under the same conditions, the current would be substantially less.

One alternative is to use a Neon screwdriver as above. This is a transparent screwdriver, with a metal cap at the end you hold it, and a neon bulb with a resistor inside. Touching the 120 while you are touching the other metal end, the neon will glow, telling you there’s voltage. But you may not have such a fancy tool. And incidentally, if you have it, and use it, the current through it and you is more than that through the digital multimeter and you.

Another alternative is to use a long wire for one of your meter’s leads to a reliable zero voltage reference, like the earth. But if you’re on the 37th floor, you may not have the luxury of having a wire long enough.

So some tools tell you what may appear to be legitimate, when in fact it’s not. You are the only and ultimate insurance to make absolutely sure the displayed information is legitimate, instead of bogus.

Use not your head, and you may lose it.

Use it incorrectly, and you may still lose it.

Use it correctly, and you may save the day.

Cheers,

Sal

www.emfrelief.com

Another great read thank you